The bypass study is “a sobering reality check” for people hoping that the newer drug-coated stents “would level the playing field” and make these treatments equally effective, Harvard University cardiologist Dr. Joseph Carrozza wrote in an accompanying editorial.

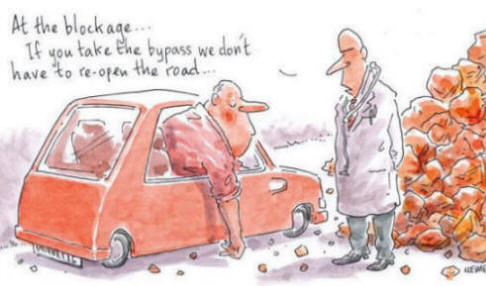

Blocked arteries cause chest pain by depriving the heart of needed blood, and can lead to a heart attack. One solution is bypass surgery, which reroutes blood vessels to detour around blockages. Angioplasty has emerged as a non-surgical alternative, in which a balloon is pushed into a blood vessel and inflated to flatten the clog, and stents are placed to keep the artery open.

Bypass has become less common as angioplasty has risen dramatically. In 2005, about 469,000 bypasses were performed on 261,000 patients. More than 1.2 million angioplasties were done, though many people had more than one procedure.

In 2005, Edward Hannan of the State University of New York at Albany published a study that found bypass to be better than angioplasty with bare metal stents for patients with multiple blockages. His new study makes a similar comparison, but with the newer drug-coated stents, which came out in 2003.

Bypass patients had fewer

heart attacks

Researchers analyzed two state

databases of 17,400 New York residents treated

for multiple blockages in 2003 and 2004, and

compared deaths and complications 18 months

later.

Survival rates for both treatments were excellent, but bypass still showed a significant advantage after researchers took into account differences in how sick or old the patients were.

People with three clogged arteries had a survival rate of 94 percent after bypass compared with about 93 percent after stenting, which translated to a 20 percent lower risk of death. Those with two blockages had a survival rate of 96 percent after the operation compared with roughly 95 percent after stenting — about a 30 percent lower risk of death. The bypass group also needed fewer repeat procedures and suffered fewer heart attacks after treatment.

The New York State Department of Health helped pay for the study. The research covered the period in 2004 when former President Bill Clinton had quadruple bypass surgery, but it isn’t known if his case was included, or if angioplasty was an option.

Stents still might be better for older patients and others who face greater risks from surgery, or for people who strongly prefer a less drastic treatment, Carrozza wrote. Some types of blockages also cannot be treated with stents.

Stent sales suffered last year after some studies suggested the drug-coated versions might lead to deadly blood clots months or years later. Danger was thought to be greater when stents were used “off label” for blockages other than types approved by the federal Food and Drug Administration.

The second study gave some reassurance that this may not be so risky. A team of U.S. and Canadian scientists looked at 6,551 patients who received either drug-coated stents or plain metal ones. Among those who received stents off-label, no difference in heart attacks or deaths was seen, though the bare-metal stent group needed more repeat procedures.

The findings “appear to validate off-label use” of drug-coated stents, but this single observational study is not enough to declare that safe, Carrozza wrote.